The human body is very complex, with several openings and several exits. But exactly how many holes does a person have?

This seems like an easy question to answer. List job information and add them up. However, when you start thinking about questions like “What exactly is a hole?”, it’s not so simple. “Do openings count?” and “Why can’t mathematicians tell the difference between a straw and a donut?”

you may like

But if you’re digging a “hole” on the beach, your goal probably isn’t to dig all the way to the other side of the world. Many people think of holes as depressions in solid objects. But “it’s not a real hole because it has an end,” Stekels said.

Similarly, James Arthur, a UK-based mathematics communicator, told Live Science that “a ‘hole’ in topology is a hole through which you can put your finger into an object.”

When digging an undersea tunnel like the Channel Tunnel between Britain and France, engineers first dug two openings. But as soon as these two drilling projects were combined, the Channel Tunnel became a fundamentally different object (what Arthur and the engineers called a “throughhole”). It’s like a straw or a tube with an opening at each end.

And if you ask people how many holes there are in a straw, you’ll likely get a variety of answers, from one to two to zero. This is a result of our colloquial understanding of what constitutes a hole.

To find a consistent answer, we can turn to mathematics. And the problem of classifying how many holes an object has falls squarely in the realm of topology.

For topologists, the actual shape of an object is not important. Rather, “Topology focuses on the fundamental properties of shape and how objects are connected in space,” Steckles said.

In topology, objects can be grouped by the number of holes they have. For example, a topologist won’t know the difference between a golf ball, a baseball, or even a Frisbee. If they were all made of clay or putty, Stekels argued, they could theoretically be crushed, stretched, or otherwise made to look similar to each other without drilling or closing holes in the clay or gluing different parts together.

you may like

But to topologists, these objects are fundamentally different from bagels, donuts, and basketball hoops, each with a hole in the middle. A figure eight with two holes and a pretzel with three holes are also different topological objects.

A helpful way to understand how mathematicians think about the straw problem is to “imagine that our straws are made of play dough,” Arthur said. “Let’s take this straw and slowly push the top down, making sure the hole in the middle remains open, until it looks like a donut.” Arthur said a mathematician would say, “A straw is in phase with a donut.”

Perhaps the elongated aspect ratio of the straw and the fact that the two openings are relatively far apart suggest two holes. But to a topologist, a bagel, a basketball hoop, and a donut are all topologically equivalent to a straw with a single hole. “The hole in the straw goes through the straw, and the opening on the other end is just behind the same hole,” Stekels says.

return to human body

Using topologists’ definitions of holes, we can address the original question: How many holes are there in the human body? First, let’s list all the jobs we have. The most obvious ones are probably the mouth, urethra (where urine comes out), anus, and nostrils and ears. Some of us also have milk ducts in our nipples and vagina.

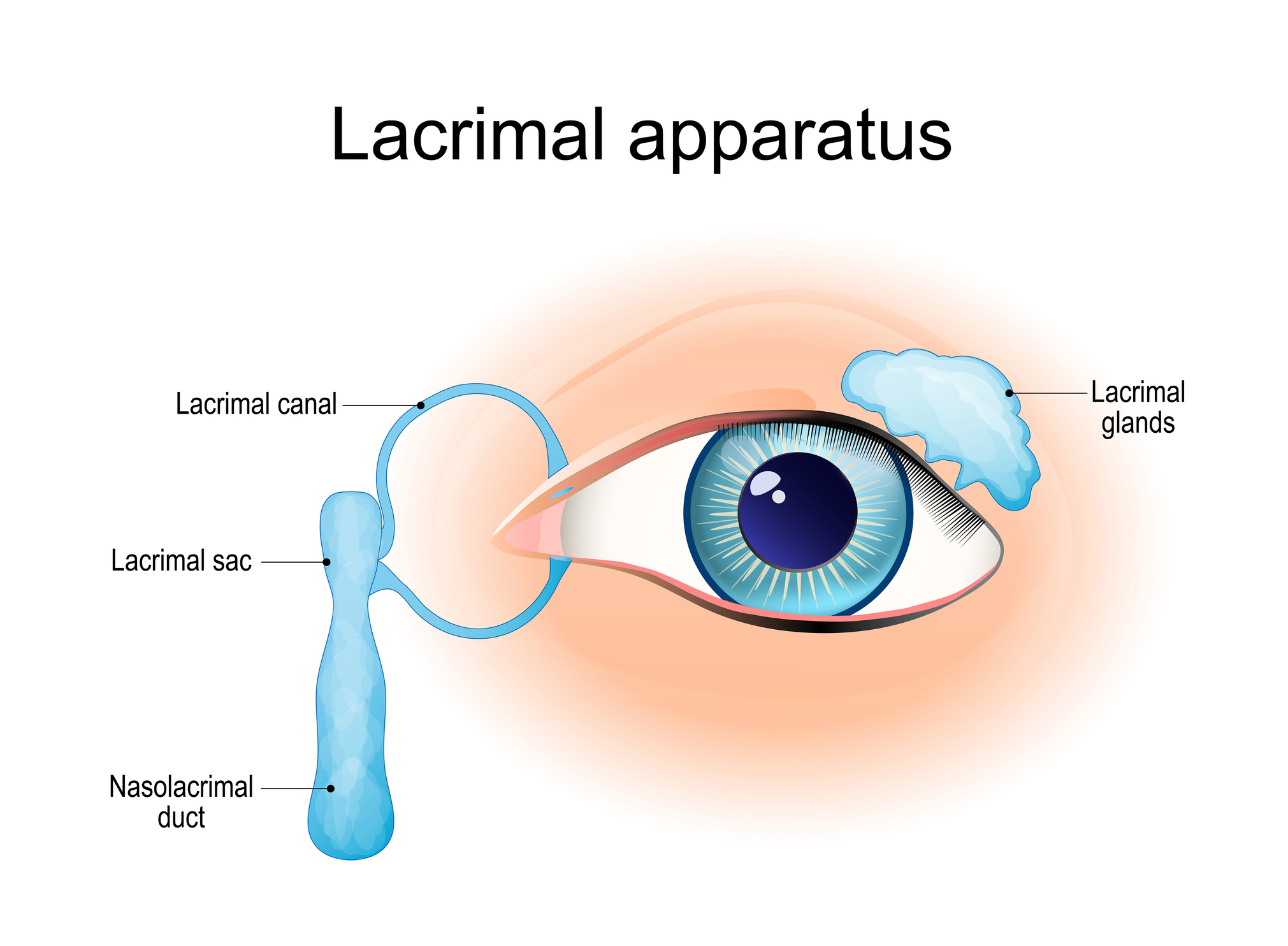

We also all have four not-so-noticeable openings in the corners of our eyelids closest to our noses. The four puncta drain tears from the eyes into the nasal passages. On an even smaller scale, there are pores that allow sweat to drain from the body and sebum to lubricate the skin. Our bodies may have millions of these orifices in total, but do they all count as holes?

To make the question more interesting, consider whether you can thread a very thin string through one hole and out the other. Setting the size of this thread to about 60 microns (60 millionths of a meter) allows the thread to enter openings as small as pores. But, and this is important, you can’t walk away from it. You won’t be able to get out the other side. It is blocked by cells at the bottom of the pore. The cells are too thick to pass through the vascular system that supplies nutrients to the pores.

“They’re not really holes in the topological sense, because they’re not completely penetrating,” Steckles says. “They’re just blind holes.”

This definition excludes all pores, milk ducts, and urethra. It was not possible to thread the string through one of these openings and out of another. The ear canal is also separated from the rest of the sinuses by the eardrum, so it must pass through it.

“We have a mouth, anus, and nostrils. These are four of the orifices that form the pores,” Arthur said. “But there are actually eight. The other four come from the tear ducts, two at the top and two at the bottom of each eye.”

However, this does not mean 8 holes. Steckles pointed out that “holes that pass through a shape become difficult to count if they are connected within that shape.”

see underwear

For example, underwear has three openings (one at the waist and one on each leg), but it’s not immediately clear how many holes topologists say underwear has. “A useful trick is to think about flattening it,” Stekels says. — “If you stretch the waistband of your pants over a large hula hoop, you’ll see two hems of the pants sticking out, each with one hole.”

So even though there are three openings, there are only two holes in the underwear. “So if the holes connect in the middle, the number of holes is one less than the openings,” Steckles argued. Correspondingly, the topology shows that the human body has seven different orifices, albeit eight interconnected orifices.

But there may be another one. Often seen as a blind hole, the vagina connects to the uterus, which in turn connects to one of the two fallopian tubes. These tubes are open at their distal ends and open into the peritoneal cavity near the ovary. It is the job of the finger-like projections of the infundibulum at the end of the fallopian tube to catch the egg as it is released from the nearest ovary. However, it has been demonstrated that an egg released from one ovary is captured by the opposite fallopian tube, allowing passage between the two open ends of the fallopian tube. So our little string could go all the way through the female reproductive tract and back and count as one more hole.

So the mathematician’s answer is that humans have seven or eight holes.

After all, the problem is not just counting availability, but understanding connections. Topologically speaking, our bodies are more like a carefully crafted costume for an octopus than Swiss cheese.

Human Skeleton Quiz: What do you know about the bones of the body?

Source link